Wednesday, 26 October 2022: A Day with Che in Santa Clara

Ernesto (“Che”) Guevara (1928 – 1967)

Up at 6:00 this morning to do my laundry. My notes describe the laundry schedule I follow to insure I have enough clean clothes. I won’t bore my readers with my “dirty laundry” but suffice it to say, it’s a challenge here because of the humidity. I’m finding that it’s taking about 24 hours for clothes to dry when I hang them in my room. Ah yes, the humidity. Since arriving in Cuba last week, I have not found temperatures all that hot (highs in the low 80s) but the humidity is making me lethargic. So I take advantage of shade and breezes when possible. My body is used to the dry, mile-high air of Denver and will take some time to adjust to the Cuban climate.

Pedro brings me a big breakfast on the 3rd floor patio: a scrambled egg, fruit (guava, papaya, banana, and pineapple), a small cheese sandwich with catsup, several baguette slices with butter, guava juice, and black tea. Price - $5.00. Pedro says that many foreigners don’t like guavas and I agree. The juice is OK but the fruit doesn’t have much flavor and is too seedy.

With Pedro’s map in

hand, I head out to learn more about Che Guevara, the internationally famous

hero of Cuba’s 1950s revolution. It’s

less than a mile to El monumento del tren blindado (armored train monument). The site is located where Avenida

Liberación crosses the main rail line across Cuba east of downtown. It includes an obelisk, a bulldozer, and railroad

box cars with displays and photos related to the train derailment that changed

Cuban history.

Left: Walking the Boulevard de Independencia on the way to the armored train monument. Right: Statue of Che Guevara east of the armored train monument.

The deciding event of the Cuban Revolution happened at this

non-descript railroad crossing in Santa Clara on December 29, 1958.

In December 1958, Che

Guevara’s vastly outnumbered guerilla forces were battling the Cuban Army for

control of Santa Clara, a key transportation and communications hub. The army had sent an 18-car armored train pulled

by two diesel-electric locomotives from Havana to reinforce its forces in the

east. The train was loaded with rifles,

ammunition, armored vehicles, artillery, supplies, and 408 armed soldiers.

Left: The obelisk

describing the attack on the armored train and its contents.

Right: Bottles used

for Molotov cocktails and an armband for Castro’s 26 July Movement.

Che commandeered a bulldozer from the school of agronomy at the local university. The dozer operator destroyed a section of rails where the rail line crosses Avenida Liberación. On December 29, 1958, the armored train derailed at this spot. Using small arms and Molotov cocktails, the rebels forced the demoralized government soldiers out of the train cars. The soldiers surrendered to the rebels who captured all the armaments and supplies from the now-crippled train. When President Batista received news of the debacle, he knew his goose was cooked. Less than three days later, he left Cuba for the last time taking with him his family and some $300 million. He was initially given refuge in the Dominican Republic by his fellow fascist dictator Rafael Trujillo and died in Spain in 1973.

Thus, the train

derailment effectively secured the victory of Castro’s rebel forces over

Batista’s government and Che Guevara gets credit for leading the brilliant effort

to make it happen.

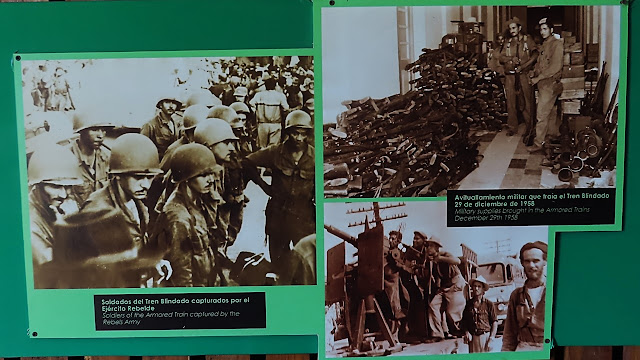

Photos showing the aftermath of the

train derailment.

Left: Government

soldiers captured by the rebel army after the train derailment.

Right: Huge cache of

arms captured by Che’s forces from the wrecked train.

When I get back to Hostal Amalia, Pedro meets me with a big wad of 45 crisp, new 500-peso bills (22,500 pesos) which he scored for me this morning in exchange for the US$150 I had given him. This will cover my peso needs for another week. I am very appreciative and tell him I hope he made some money from the deal. Pedro and I talk about the U.S. sanctions on Cuba. We agree that they are stupid. Pedro thinks the sanctions may have been OK 60 years ago but make no sense today. We also agree on the hypocrisy of the U.S. having trading relations with View Nam but continuing the Cuban boycott.

I can’t find two restaurants Pedro had recommended for lunch (I think one is closed) so it’s back to La Aldaba where I ate last night. I polish off a spaghetti Napolitano and limonada (it’s like a daiquiri without the rum). It pleasant siting here – it’s after 2:00 and the lunch crowd has left.

After lunch, I take a

1½ mile walk west to the imposing Che Guevara monument, mausoleum, and museum. The towering bronze statue of Che (more than

50 feet high) sits atop his final resting place which is located in a cavernous

room with plaques honoring 38 other men.

I ask the young guard if these are heroes of the revolution. She

replies, “Sí” but apparently my voice is too loud and she tells me to

whisper. Fortunately, I had the presence

of mind to take off my hat before entering.

For Cuba, this mausoleum feels like a sacred place, the equivalent of a

cathedral or maybe the catacombs under the Vatican. I later learn that the 38 men were killed with

Che during the failed 1967 Bolivian revolution. The adjoining museum includes photos (many

taken by Che who was a camera buff), documents, rifles, and other artifacts

from Che’s life. Unfortunately, no

photography is allowed either inside the museum or the mausoleum.

Frieze depicting Che Guevara at the head of the rebel column on its way to Santa Clara and statue of Che with his quote: HASTA LA VICTORIA SIEMPRE (Ever onward to victory).

The story of Che’s short life (he was 39 when he was executed by a Bolivian Army sergeant) is compelling. He was born to an upper class family in Argentina and made two extensive trips through Latin America while a medical student. He was deeply offended by the poverty he encountered during his trips and later as a young doctor in Mexico. There he met Raul and Fidel Castro and, in 1956, accompanied them and a small group of revolutionaries to Cuba with the intent to overthrow the government of the corrupt fascist president, Fulgencio Batista.

Guevara was hated by many U.S. government officials and conservatives for telling the truth about capitalist exploitation of the Latin American poor and his work to address inequality through armed revolution. He recognized the terrible injustices which the United States supported south of our border such as the right-wing coup overthrowing the democratically-elected government of Guatemala in 1954. Of course, his antidote to predatory capitalism, enforced by fascist thugs like Batista, was communism. As I am learning in Cuba, communism may be appealing in theory but it’s a failure in practice.

A tribute to Che Guevara (the cigar smoking soldier with beret in these photos) at the armored train monument.© Will Mahoney 2022

All rights reserved. No part of this blog post nor any associated photo can be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical or photocopying, recording, or otherwise without prior written permission of the author and photographer.

Comments

Post a Comment