Montenegro: An Overview of Some Superb Mountain Environments

After our late-night return to Podgorica from Albania, Velibor Spalevic, Klaas Annys, and I slept in late at Veli’s condo. It was past noon (8 September 2012) before we headed north on a two-lane highway toward the Dinaric Alps of northern Montenegro. Our route followed the Morača River, first through a wide plain but soon up a narrow canyon where the southward-flowing river had cut its way through Mesozoic limestone. Little villages, farms, and Orthodox monasteries hugged the steep slopes above the canyon in some places; elsewhere there were only lush mixed forests and barren and jagged limestone outcrops. The highway made its way along steep cliffs, across bridges, and through several short tunnels.

Returning to the highway, our route took us over, under, and past several old and modern arch bridges which I enjoyed photographing. “These are nothing compared to the Tara River Bridge,” Veli assured me. “We must hurry to get there before dark.” At Mojkovac, we turned east on a narrow highway following the dramatic Tara River canyon and entering Durmitor National Park. It seemed to take forever to get to the bridge on the winding highway but we made it while there was enough light left to photograph this engineering marvel from several different vantage points on both sides of the river. This concrete arch bridge, completed in 1940, is 366m (nearly ¼ mile) long and 172m (564 feet) high. Yugoslav partisans blew up the central arch in 1942 which temporarily halted the Italian offensive in Montenegro. Following the war, it was rebuilt.

We had drinks at an open air café next to the bridge and Veli talked with a local man who organized rafting trips on the Tara. Veli wanted us to go rafting the following day (Sunday, the 9th), but I said “no thanks.”

At our seminar at the University of Montenegro a few days earlier, Klaas had given a photo-illustrated PowerPoint presentation about Durmitor geomorphology and Montenegro’s only glacier where he had been doing field research for his Master’s thesis during the summer. I was seduced by Klaas’s photos and had immediately told him and Veli that I would love to hike up to the glacier. Klaas said he would be happy to take me there when we got to Durmitor National Park. Veli thought I should wait until Monday, the 10th, to do the hike with Klaas. The forecast for the 9th called for perfect late summer weather but the 10th was predicted to be cloudy with possible showers. Thus, I wanted to take advantage of the sunshine. I was also sick of so much sitting in cars, trains, and planes so the idea of sitting in a raft all day didn’t appeal. Instead, I needed a good workout, and a hike to the glacier sounded perfect.

We spent the night in Veli’s large, comfortable cabin at the ski area near Zabljak, about 25km west of the bridge. Early the following morning, Klaas and I headed for the glacier, normally an easy two hour hike for fit, 22-year-old Klaas, but a tough three hour workout for my aging and out-of-shape bones. Veli couldn’t do the hike because of a bum knee, so he took off to spend time with his family.

Recently, Veli recommended a 1986 article titled “National Park Durmitor” by Mihailo Vuckovic in the journal Agriculture and Forestry (published by the Biotechnical Faculty at the University of Montenegro). Following are some points of interest about the park which I gleaned from the article:

· The park was planned in 1952 and was established in 1978 to protect ecological and cultural values of the area. In 1980, it was declared a UNESCO Natural Heritage Site.

|

Our route from Podgorica (formerly Titograd), Montenegro’s capital,

to Zabljak, a small resort town next to Durmitor National Park.

|

|

| The highway is on the ledge on the right side of the Morača River Canyon. |

|

| An Orthodox monastery (bottom center of photo) below the towering Sinjavina Range with peaks of Cretaceous-age limestone reaching elevations of more than 7000 feet. |

After a couple hours of driving, Veli provided us a welcome stop at the Biogradska Gora National Park near the town of Kolašin. It is a relatively small park (only 54km2– about 13,350 acres) but features an old-growth forest of mixed deciduous and fir species, mountains reaching 2000m (6560 feet) elevation, and a great diversity of flora and fauna. Veli was well known by park employees as he had helped obtain USAID money to build a group of attractive log cabins which are available for rent by park visitors. While Veli chatted with one of the park rangers, Klaas and I took a brisk walk around Biogradsko Lake (the park’s largest) and noted that the water level was quite low this year.

|

| Naturally eroded steep cliffs in Biogradska Gora National Park. |

|

| The water level in Biogradsko Lake was way down this summer. |

Returning to the highway, our route took us over, under, and past several old and modern arch bridges which I enjoyed photographing. “These are nothing compared to the Tara River Bridge,” Veli assured me. “We must hurry to get there before dark.” At Mojkovac, we turned east on a narrow highway following the dramatic Tara River canyon and entering Durmitor National Park. It seemed to take forever to get to the bridge on the winding highway but we made it while there was enough light left to photograph this engineering marvel from several different vantage points on both sides of the river. This concrete arch bridge, completed in 1940, is 366m (nearly ¼ mile) long and 172m (564 feet) high. Yugoslav partisans blew up the central arch in 1942 which temporarily halted the Italian offensive in Montenegro. Following the war, it was rebuilt.

|

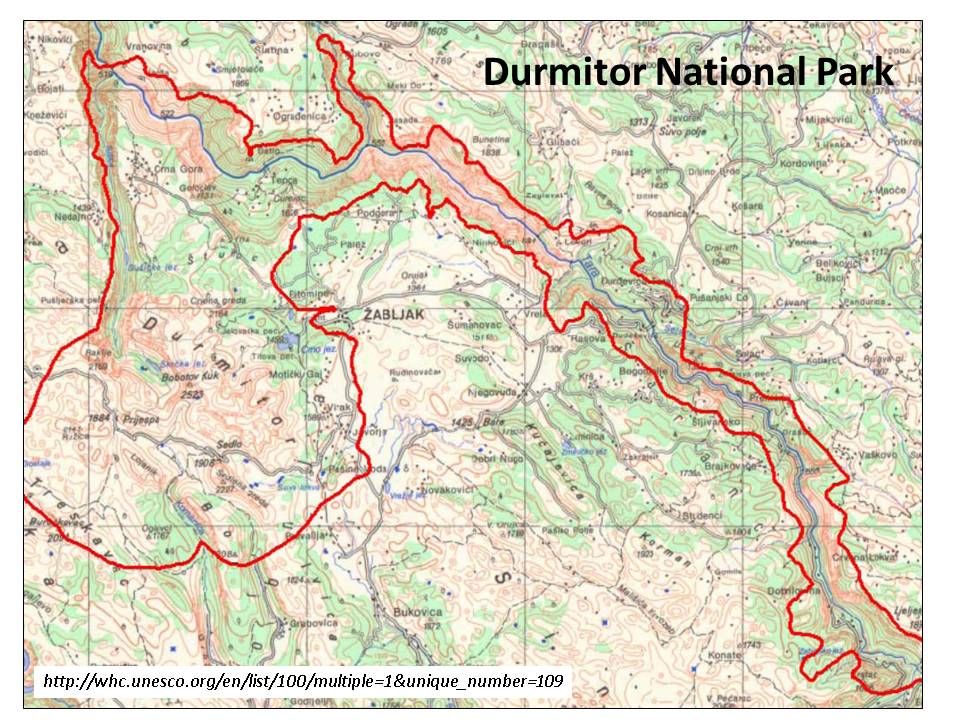

| Durmitor National Park (boundary in red) includes the Tara River Canyon and the Durmitor Range. |

|

| Our route north from Podgorica took us through a number of tunnels (top). At day’s end, we reached the dramatic Tara River Bridge (bottom). |

We had drinks at an open air café next to the bridge and Veli talked with a local man who organized rafting trips on the Tara. Veli wanted us to go rafting the following day (Sunday, the 9th), but I said “no thanks.”

At our seminar at the University of Montenegro a few days earlier, Klaas had given a photo-illustrated PowerPoint presentation about Durmitor geomorphology and Montenegro’s only glacier where he had been doing field research for his Master’s thesis during the summer. I was seduced by Klaas’s photos and had immediately told him and Veli that I would love to hike up to the glacier. Klaas said he would be happy to take me there when we got to Durmitor National Park. Veli thought I should wait until Monday, the 10th, to do the hike with Klaas. The forecast for the 9th called for perfect late summer weather but the 10th was predicted to be cloudy with possible showers. Thus, I wanted to take advantage of the sunshine. I was also sick of so much sitting in cars, trains, and planes so the idea of sitting in a raft all day didn’t appeal. Instead, I needed a good workout, and a hike to the glacier sounded perfect.

We spent the night in Veli’s large, comfortable cabin at the ski area near Zabljak, about 25km west of the bridge. Early the following morning, Klaas and I headed for the glacier, normally an easy two hour hike for fit, 22-year-old Klaas, but a tough three hour workout for my aging and out-of-shape bones. Veli couldn’t do the hike because of a bum knee, so he took off to spend time with his family.

|

| View west from Veli’s cabin with the local ski area on the left. Our hike took us through the forest and way around the peak on the right. |

The hike was the perfect respite after so many weeks of hectic travel. The glacier is located at the end of a northeast-trending U-shaped valley. I was surprised at how small the glacier is –it didn’t seem much larger than a football field. Its elevation is slightly less than 2000m (about 6500 feet). When we arrived in late morning, part of the glacier was being bathed in warm sunshine and tiny channels at its surface were carrying off melt water. The little glacier doesn’t seem to be located at an optimum location, and I wondered how it was managing to survive. Klaas attributed the glacier’s success to the large volume of snow that sloughs and avalanches off the steep adjacent cliffs and collects in the small basin in which the glacier is located. Thus, not only does it receive a large volume of snowfall in the winter, but as temperatures warm in the late winter and spring, the heavy wet snow on the cliffs above cascades down into the glacial basin.

|

View southwest up the route to the glacier.

Note that there is no stream in the valley. All water flow

is subsurface through the porous limestone bedrock.

|

|

Trail to the glacier is in the bottom center of the photo.

The glacier itself is barely visible in the shadows just below

the precipitous cliff slightly to the right of center of the photo.

|

|

Left: I’m standing at the bottom of the glacier for scale (Photo by Klaas Annys).

Right: Klaas standing in front of an outcrop of Cretaceous limestone with distinctive vertical jointing.

|

I’ve since learned (from the reference listed below) that higher elevations in the park receive an average of 1700mm (67 inches) of precipitation annually and more than half of that is snow. At higher elevations, snow depth can reach two meters (6½ feet) by late winter. The mean annual cloudiness at Zabljak (elevation 1400m) is nearly 60%. Even in August, the sunniest month, it is cloudy there more than 40% of the time. We can assume that the glacier at 2000m elevation receives even less sunshine. And with nighttime temperatures dipping below freezing most of the year, it starts to make sense why this little glacier continues to thrive. I don’t know how climate change may be affecting the glacier but higher air temperatures might mean more precipitation in this area and thus an enhanced snow supply.

|

Glaciers act like very slow moving freight trains transporting large volumes

of rock debris down valley. Note small rivulets of melt water in the foreground.

|

Looking down the glacier with a small moulin in the right foreground. A moulin is a roughly circular opening in a glacier through which surface melt water enters. If you’d like to learn more about glaciers and see some awesome photography from places like Greenland, Iceland, and Alaska, I’d strongly recommend the new film Chasing Ice which may win the 2012 Academy Award for Best Documentary.

Recently, Veli recommended a 1986 article titled “National Park Durmitor” by Mihailo Vuckovic in the journal Agriculture and Forestry (published by the Biotechnical Faculty at the University of Montenegro). Following are some points of interest about the park which I gleaned from the article:

· The park was planned in 1952 and was established in 1978 to protect ecological and cultural values of the area. In 1980, it was declared a UNESCO Natural Heritage Site.

· It is 390km2 in area (96,350 acres).

· Elevations within the park range from 512m (1680 feet) to 2523m (8275 feet) at the summit of Bobotov kuk, the second highest mountain in the Dineric Alps.

· The primary geologic influences on the landscape have been tectonic uplift and glacial erosion.

· The mountain peaks are comprised of Jurassic-age reef limestone.

· The lower slopes are upper Cretaceous-age Durmitor flych, a complex assemblage of marl, clay schist, marlish limestone schist, breccia, and clastic rock.

· Much of the surface is mantled by Quaternary glacial moraine deposits composed of fragments of Triassic, Jurassic, and Cretaceous rock.

· Several rivers besides the Tara are located in the park as well as underground watercourses and karst springs typical of an area of porous limestone bedrock.

· There are 16 mountain lakes within the park and all are of glacial origin.

· The largest of these lakes is Crno jezero (Black Lake) with a surface area of 0.52km2 (128 acres). An interesting feature of this lake is its lack of a surface outlet. All drainage from the lake is subsurface – northeast to the Tara River and southwest to the Piva River. Thus, the lake is located on the drainage divide between two watersheds which is very unusual!

· January temperatures average -6 to -2oC (21 to 28oF) in Zabljak (elevation 1400m) and 12 to 16oC (54 to 61oF) in July. Temperatures reach 25oC (77oF) for an average of only 8 days/year in Zabljak but up to 31 days in warm years.

· There are 9000ha (22,250 acres) of forest within the park with black pine and beech the dominant species. Spruce-fir forests are present at higher, more humid elevations. The park supports a great diversity of plants.

· The park is home to bear, deer, wolves, and smaller mammals; raptors (including the golden eagle and griffin vulture) as well as fowl and songbirds.

· The Tara River supports brook trout, grayling, bullhead, and other fish species.

· The medieval town of Pirlitor (originated in the 14th Century) and ruins of 16th Century monasteries are located within the park.

· There are important sites within the park related to the Yugoslav partisan cause against the fascists during World War II including a former headquarters and hospital.

In my next post, I head north to Budapest, Hungary.

Comments

Post a Comment