Southeastern Europe: Four Countries in 24 hours

After finishing our seminar presentations at the University of Montenegro on 6 September 2012, Professor Velibor Spalevic, grad student Klaas Annys, and I rushed back to Velibor’s condo, got our travelling gear together, and headed northwest from Podgorica toward the Bosnian border. Ostensibly, we were on a trip to look at erosion and sedimentation issues but the first 24+ hours were more of a tour of some stunning mountain and coastal landscapes. Including a few short photo stops and a border crossing, it took several hours on a winding 2-lane highway through the mountains to reach our first destination, Trebinje, the southernmost town in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

|

| Fountain in central Podgorica, the capital of Montenegro. |

|

| The rugged Dinaric Alps (Dinarides) near the Bosnia-Montenegro border are mainly composed of Mesozoic-age limestone and dolomite. |

|

| Map showing our route on September 6 from Montenegro to Bosnia and Croatia and back to Montenegro |

Trebinje is within the Republika Srpska and located in the valley of the Trebišnjica River. Upon arrival, Veli first drove us to the top of Crkvina Hill overlooking the town where we had an excellent view of the sunset. As darkness began to fall, we drove into the old walled center of the town. Klaas and I wondered around on foot and found some good slices of pizza to go.

|

| View of Trebinje at sunset from Crkvina Hill |

|

| Interior of Gračanica, a Serbian Orthodox monastery located on Crkvina Hill |

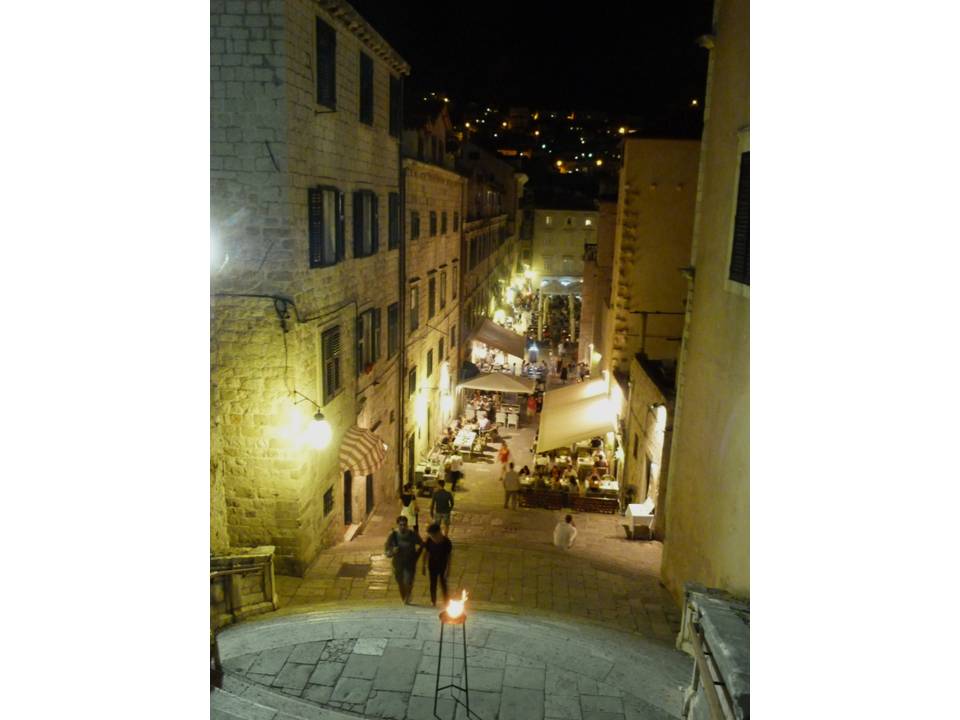

After spending less than two hours in Trebinje, we drove west over the mountains to the Croatian border, then descended to Dubrovnik on the Adriatic Sea. A warm September evening was a perfect time to visit the historic walled city, and we wandered its narrow pedestrian-only streets with off-white buildings brightly illuminated by floodlights. It’s no wonder that Dubrovnik is a popular tourist destination. According to Veli, few locals still live in this old walled portion of the city. They’ve sold out to wealthy foreigners who only spend a few days or weeks a year in the city. Thus, it’s nearly deserted in the off season.

Like Bosnia, Croatia was part of the Yugoslavian Federation until its breakup in the 1990s. Croats and Serbs have had a difficult coexistance going back hundreds of years. Although both are ethnic Slavs and speak essentially the same language, Croats are predominantly Roman Catholics while Serbs are Eastern Orthodox Christians. In the 20th Century, Yugoslavia was occupied first by Italy, then by Germany during the Second World War. Some Croats collaborated with the Nazis while Serbs tended to support the Allies. And during the conflict in the early 1990s, Croats and Bosnian Muslims sided with each other as both wanted independence from the Yugoslav government in Belgrade which had become dominated by Serbs after Tito’s death in 1980.

|

| Stone walls of old Dubrovnik glow in the electric illumination. |

It was getting late when we left Dubrovnik and headed to the southern tip of Croatia’s long finger of territory bordering the Adriatic. We crossed yet another international border back into Montenegro, then followed the sinuous Bay of Kotor to the resort town of Herceg Novi where Veli had arranged for our accommodations with a friend who owns a hotel there.

It was around 1:00AM before I got to bed, so I was rather grouchy when Klaas rapped on my door around 6:30AM telling me that Veli wanted to leave soon. Our destination for the day was Tirana, the capital of Albania, where Veli had arranged an afternoon meeting at the Albanian Directory of Land & Water. We had a long drive ahead of us on winding and/or crowded two-lane highways before we would reach Tirana. The sunny day and jagged Montenegrin coastline helped revive me from my lack of sleep. After about ½ hour of driving, we took a 10-minute ferry ride across a narrow section of the beautiful Bay of Kotor, then continued along the “Tivat Riviera” (named for the town of Tivat), and eventually stopped for mid-morning coffee at a luxury hotel in the resort town of Budva where we sat at a table overlooking the harbor. The scenery was lovely with mountains rising up from the rocky coastline. However, with my misanthropic dislike of resorts, I felt once again that humans had paved paradise and heavily peppered it with bland high-rises, chic shops, and trendy restaurants for the idle rich and the unimaginative middle class masses who don’t mind cheek-to-jowl crowds on beaches and are willing to pay 20%+ interest on their credit card balances after a week in one of these seductive Plasticvilles. Veli confirmed what I’d previously heard about the Montenegrin coast: It has become a favored vacation spot for the Russian nouveau-riche who have been buying up condos at a feverish pace improving the Montenegrin economy but perhaps stealing some of the little country’s soul.

|

| Morning sun on the Bay of Kotor |

|

| This uninspiring Montenegrin beach resort could be anywhere that has warm sunshine and a coastline. |

|

| Map of our route on September 7 from Herceg Novi, Montenegro

(upper left corner of map) to Albania and back to Podgorica, Montenegro.

|

Albania differs from the other countries on this whirlwind Balkan trip in that it was never part of Yugoslavia. Also, Albanians are not Slavs, they are not Greeks, they are not Macedonians. They are (excuse me for being trite) Albanians – a distinct ethnic group with a distinct language whose members are not only dominant in Albania but also in the adjacent former Yugoslav republic of Kosovo. Large numbers of ethnic Albanians are also found in Greece, Turkey, Italy, and other parts of Europe. A majority are Muslims; the remainder are Eastern Orthodox or Roman Catholics. Like most Balkan countries, Albania has had a turbulent history of failed kingdoms, foreign domination (including Ottoman Turks and World War II fascists), and a difficult experiment with communism from 1945 until 1991 mostly under the leadership of Enver Hoxha, who died in 1985. Formerly the poorest country in Europe, Albania appears to be making rapid strides economically and is now a candidate to join the EU.

On our way to Tirana, I could see evidence of Albania’s struggle to emerge as a modern country. Most of the 100km (62 mile) trip from the northern Albanian city of Shkodra followed a two-lane highway that was packed with late-model cars, trucks loaded with imports and exports, and slow-moving tractors pulling wagons stacked with produce from the recent harvest. After creeping along for the first 50km, we suddenly hit a section of new four-lane expressway where Veli cranked it up to about 120 (kph, not mph!). But after 10km we were back on a two-lane highway which continued until we hit Tirana’s wide boulevards leading to the modern city center. Much of our trip through northern Albania passed through a spacious, inland agricultural valley, warmed by the mild Mediterranean climate and watered by streams emanating from lofty mountains to the east. It occurred to me that this valley had the potential to become an agricultural cornucopia much like California’s San Joaquin Valley. We arrived at the Agricultural Ministry buildings about an hour late where the congenial officials from the Directory of Land & Water were waiting for us.

|

| Bumper-to-bumper traffic on the main highway heading south to Tirana. |

Comments

Post a Comment